7 Books in 7 Days

- Steven E. Newton

- Oct 28, 2021

- 6 min read

On Photography

Susan Sontag’s On Photography. First published in 1977, the book is a collection of essays written for The New York Review of Books. I picked up my copy, the one with the cover shown in the photograph, in the early- to mid-80s. The book is notable in critiquing the key lines of thought that had been said about photography up until then. This book was my first introduction to thinking about photography and communication. The central thesis of Sontag’s essays is that a photograph can, and usually does, lie. Photographs are no more objective than the photographer behind them. They depict reality as subjectively as the photographer sees it.

The industrialization of photography permitted its rapid absorption into rational — that is, bureaucratic — ways of running society. — Susan Sontag

It is likely the most widely read and influential book on the meaning and place of photography in culture -- as art, knowledge, and morality. The chapters titled "In Plato's Cave" and "Photographic Evangels" informed my growing media literacy and today are even more relevant. It’s possible to be in the photography business without understanding the medium deeply. By understanding photographs in media and culture both photographers and non-photographers are better able to analyze and interpret the messages they send.

The Keepers of Light

I picked this one up, used, for a history of photography class I took in college. The Keepers of Light: A History and Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes, by William Crawford. If all the photographic suppliers in the world shut down, this 1979 book is where I’d turn. With the information here and access to a chemical supply house a persistent experimenter could re-invent photography almost from scratch.The book is divided into two sections: Section I covers the early history of the photographic process and its antecedents. There’s a fascinating story line of how early photography was influenced by metal engraving, woodcut, and painting, and how photographers attempted to accurately represent the world up until Alfred Steigliz broke with tradition. The book Alfred Stieglitz and the Photo-Secession by William Innes Homer covers that history in depth.

What photographers really do … is contend with a medium that forces them to look, to respond, and to record the world in a technologically structured and restricted way. —William Crawford

Section II has chapters detailing techniques and materials for processes, including my favorite — platinum and palladium printing. There’s even a section on making paper, in case that art were to be forgotten. Note that he does not include the techniques for the daguerreotype process, because, well, mercury poisoning. Like yesterday’s selection, Susan Sontag’s On Photography, this book helped me learn to “see” and realize that photographs don’t have to look a certain way.

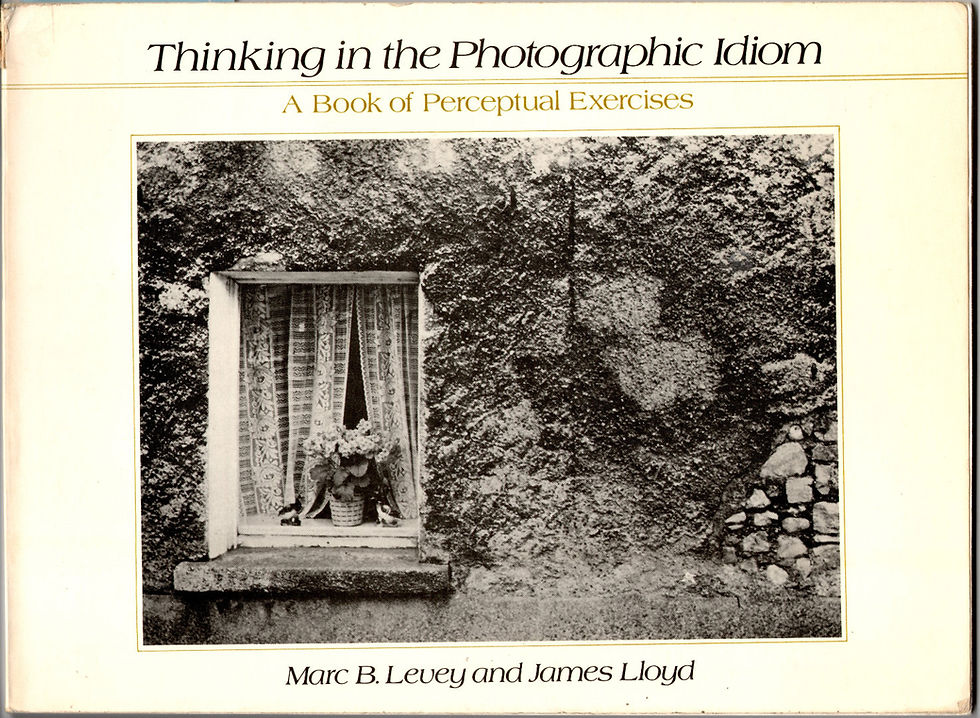

Thinking in the Photographic Idiom

In this slim (130 pages, including bibliography) 1984 volume, Thinking in the Photographic Idiom: A Book of Perceptual Exercises, by Marc B. Levy and James Lloyd, gives 36 short exercises on visual and photographic seeing. A tag on the inside of the back cover says I bought it new at Texas Art Supply, which still going strong some 30 years on.

The exercises range from the purely technical aspects of portrait lighting, to very personal subjects like “Overcoming Creative Block” and “Discovering Who You Are”. The chapter “Introduction to Visual Modifiers” includes this flow chart on the photographic process:

This book is full to bursting with gems of photographic tips and everything in this book applies to digital photography as well as film. There are a couple of exercises, such as the photomontage one in number 19, “The Photographic Innovations”, that mention film, but they can be done equally well with pixels. Definitely look for a copy of this book if you feel out of ideas and need something to inspire you.

Black & White Photography: A Basic Manual

I had a hard time deciding between two very good books for today. I nearly went with David Vestal’s The Craft of Photography, but upon closer inspection I find that I’ve marked up Black and White Photography: A Basic Manual by Henry Horenstein a great deal, reminding me how much I got out of it. My edition is dated 1983 (there’s a third edition as well, first published in 2004) and the stamp on the inside front cover suggests I bought it or used it when I was in graduate school in 1988-1989. So, after three books about the nature and history of photography, we finally get to one that teaches practical camera and darkroom skills. Any sufficiently motivated photographer will find everything needed to learn the basic skills of shooting, developing, and printing black and white film.

The first five chapters cover using the camera and properly exposing the film. Chapters 6 and 7 cover developing the film and understanding problems that might arise and how to correct them. Chapter 8 is all about printing, and at the end are three chapters for miscellaneous additional topics. Appendix 3 is a concise list of common negative and print problems with a description, a probable cause, and a remedy listed for each defect. This reference alone would almost recommend the book. The couple of times I’ve given darkroom workshops I taught from this book.

The New Zone System Manual Revised Edition

Next up, The New Zone System Manual, Revised Edition by Minor White, Richard Zakia, and Peter Lorenz. Copyrighted 1976 but my copy indicates it was printed in 1984. My copy also happens to have darkroom chemical stains on it.

Not a book for the casual snapshooter, this book is full technical terminology, graphs, illustrations, and directions for many tests and calibrations of the process. For example, the caption to the illustration on page 113 says “When the camera is shutter is clicked, log luminance scale (1) of the scene becomes the log exposure scale (2) of the film. After the film is developed, negative density scale (3) is obtained. This scale is elastic and can be increased or decreased by N+ or N- development.”

“The most important thing to be learned from practicing the zone system is the concept of previsualization.”

On the other hand, the lead author is Minor White, quite a character in the photography world. His writings on photography are some of my favorite. True to character, the book has a few lighthearted elements interspersed with all the Serious Photography stuff.Don’t get this book if you aren’t a film photographer with access to a darkroom and skills to use it. But if you can put the time and effort into working through it, you’ll have control over your results in a way that outwits any whiz-bang digital camera. It will take time, but as White said, “No matter how slow the film, Spirit always stands still long enough for the photographer It has chosen.”

Henri-Cartier Bresson

(Aperture History of Photography; Book 1)

So far we’ve learned about photography as a medium of expression and communication, and gone through the technical work of learning to be a film photographer. Let’s now look at some great photographs and see how they will teach and inspire us. This book, Henri-Cartier Bresson (Aperture History of Photography; Book 1) has been in my collection since the 80s. Tucked into the inside cover was a carefully typed letter I wrote to the Texas Photographic Society, dated May 13, 1992. Cartier-Bresson was the first photographer whose work amazed me. His choice of a small camera -- the 35mm Leica I -- changed the nature of photography.

There are not many words in this book. The Aperture Series format is spare: there are 97 photographs and on every spread the left-hand page is blank, the right-hand page is the image, no caption. It’s like a museum exhibit. The captions are all in the back, on page 89. There’s an artist’s statement at the beginning.

To take photographs means to recognize - simultaneously and within a fraction of a second - both the fact itself and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that give it meaning. – Henri Cartier-Bresson

Cartier-Bresson invented the concept of “the decisive moment”. In the intervening decades the term has been widely misunderstood and misquoted. Looking at the photographs in this book can show you what he meant.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

The spine of my 1980 edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is faded from sitting on a bookshelf that was by a sunny window. This book, first published in 1941, has all sixty-two of Walker Evans’ photographs on plates gathered at the front of the bo

ok, followed by all the text.

I include this book because it’s the prototypical example of the sort of documentary photography I aspired to during my education, and would still pursue given an opportunity. Photographer Walker Evans was on leave from the Farm Security Administration for the work that lead to this book. Luckily for us because that means that the resulting photographs are property of the US Government, and can be used or reproduced anywhere with few restrictions. So enough words, just go look at the pictures.

Photography: The First 150 Years

Bonus book! Photography: The First 150 Years, a special edition of the Photo☆Letter from the Texas Photographic Society. This 1991 book is #248 of 500 signed copies. It’s derived from the 1989 exhibition of the same name.

It’s special to me because it came from the Austin, Texas and University of Texas photographic community at the time I was there. It was edited by one of my professors, Julianne H Newton, and designed by another of my professors, William Korbus.

Comments